You can imagine what was going through my head as I first studied Mrs. Curwen’s book. I had been teaching piano for approximately ten years when a good friend mentioned her book.

My husband and I had decided to pursue a path of homeschooling our children. We were embarking on a journey to use a education philosophy penned in the late 1800s and early 1900s by a lady named Charlotte Mason.

As we began our journey of studying this education philosophy, we were on a path of no turning back. The educational philosopher I mentioned above recommended Mrs. Curwen’s philosophy.

In her first volume, Charlotte Mason says,

“Mrs. Curwen’s Child Pianist method is worked out, with minute care, upon the same lines; that is, the child’s knowledge of the theory of music and his ear training keep pace with his power of execution, and seem to do away with the deadly dreariness of ‘practising.'”

Being a pianist and a piano teacher, it made complete sense to me to begin studying this philosophy written around the turn of the century. I’m still on a hunt to discover why Mrs. Curwen’s method of teaching piano was abandoned.

Considering it’s been two years and I’m still curious about her philosophy, you can be rest assured I am impressed with her meticulousness in laying out what I consider a very well rounded approach at teaching children the piano.

As I’ve learned, research takes time. It seems as though that the more I uncover, the more I realize I don’t know. Yes, I’ve read Mrs. Curwen’s book, but I’m still piecing her method together in my head. I have much to learn as I submerse myself in the Victorian Era of musical philosophies.

So what did I learn first? What did I first put into practice? What did I immediately change?

Dividing and Focusing time in the Lessons

As I read her book the first time, I pulled out what I considered some monumental changes in how I approached piano teaching.

In Mrs. Curwen’s introduction, she talks about “the number of mental processes that have to be gone through by a little child when trying to read at sight the simplest tune. He has-

1st, to think of the name of the note on the staff.

2nd, to find the corresponding place on the keyboard.

3rd, to consider what amount of time it is to occupy; for which a knowledge of relative note-values is necessary.

4th, to make up his mind which finger to use.

And besides all this he must not for a moment lose sight of the position of his hand and arm, and he must be exceedingly careful to use his fingers properly.”

Much of Mrs. Curwen’s philosophy is based upon practicing the above four facets individually in every lesson. In every lesson (for the first six steps), she has the child names notes, names sounds on the piano, practicing rhythm, and playing finger exercises.

What else did I change immediately?

Recreative Repertoire

I changed what music I gave my students. I used to always give my students music that was just a bit difficult for them. I figured that if they practiced consistently for a week, they could learn something just a bit more difficult than last week.

The result?

They never had any music they could play well. They had no satisfaction. They had no repertoire.

Mrs. Curwen says,

“Teachers are apt to give young pupils pieces just a little beyond them, with the idea that this plan “gets them on.” Now, one bit of advice which the late Sir Charles Halle used to give his pupils was, “Let your exercises and studies be always a little beyond you, but your pieces well within your powers;” and with that maxim I entirely agree. The tempo of a piece is a part of the composer’s complete idea; and if the player cannot attain to the speed required by the spirit of the piece, or something approximate, he fails to interpret that idea. To give a pupil a piece just a little beyond his powers is either to mislead or to discourage him. If he is satisfied with his own performance his artistic judgement is being misled; if he does not satisfy his own ideal he is discouraged.”

You would think Mrs. Curwen was talking about my former habits as a piano teachers. I need to be giving children music well within their powers.

Finger Exercises

Mrs. Curwen says that,

“I believe that half a dozen exercises, each with a different and a definite aim, would do more for the children than the weary pages they wade through, if each exercise were memorised, made perfect in its slow form, and gradually developed in speed, or force, or delicacy, according to its object.”

She goes on to say,

“Much of the time thus unpleasantly wasted might be saved if the teacher paused to consider what sort of things the pupil ought to be able to do before he can be given such and such pieces, and limited the exercises to those which ought to produce just those results.”

I stopped giving my students finger exercise books. First of all, finger exercises shouldn’t be about reading notes. If a child is overwhelmed at all the running eighth or sixteenth notes on a page, I’m defeating the purpose of the FINGER exercise because the FINGER exercise quickly becomes a READING NOTES exercise.

I use finger numbers and write out simple exercises for the students. They don’t read notes anymore for exercises. And my exercises have a focused and definite aim. For example, if I’m encouraging my child to play a strong vivacious piece with a march like feel, I give them a finger exercise to mimic and imitate the sound of a march. I encourage them to play with strong fingers and a forte dynamic level.

Duets

I started playing duets with my students. I started playing lots of duets. Why?

First, the duets provided in Mrs. Curwen’s books directly reflect the skills the child just learned. Maybe they just learned about the interval of a second. Mrs. Curwen’s first duet by Swinstead gives the child an immediate application of reading music using the interval of a second.

Second, the duets develop a sense of beauty in the music. Sitting next to the teacher, they learn, for example, phrasing or dynamics. They learn to interpret what the compose intended for the music.

Third, the duets can offer the children an immediate sense of pleasure from his little bit of musical knowledge.

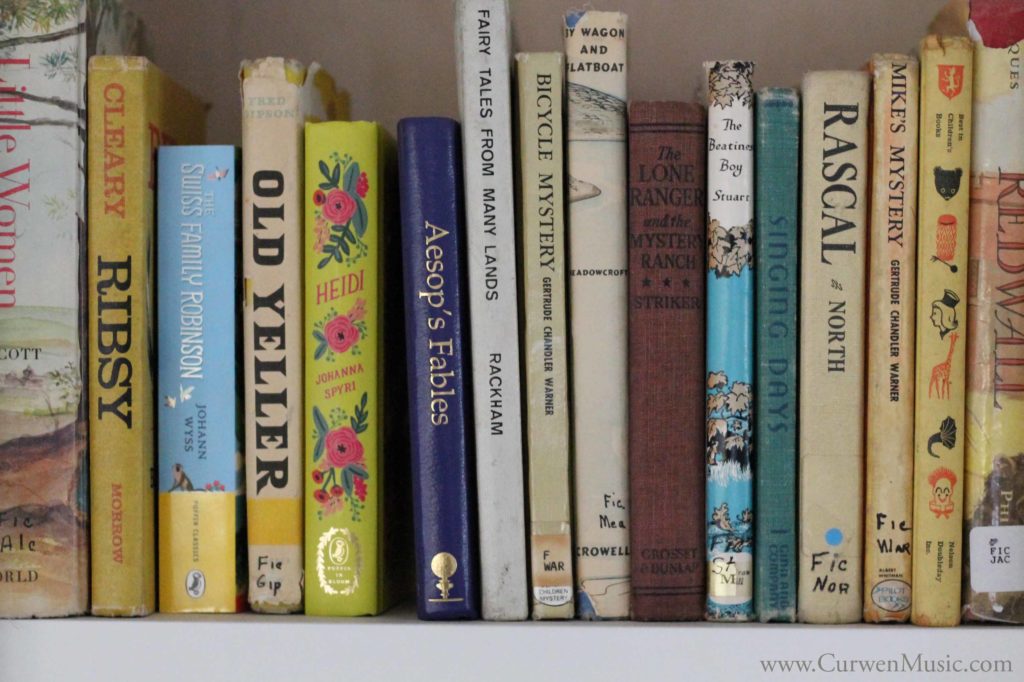

Not only do I take advantage of the thoughtfully written duets in Mrs. Curwen’s books, but I have also been searching for other books for students with teacher’s duets written for them.

Using Intervals to Teach the Staff

Mrs. Curwen’s use of intervals to teach the staff has served me exceptionally well. I have followed her recommendation to introduce intervals to all my new students within the second or third lesson. Once a child has mastered the interval of a third, we are well on our way to understand the concept of a staff.

Are you a piano teacher?

Even if you don’t fully embrace Mrs. Curwen’s methods, these may give a few refreshing ideas to consider as you teach piano lessons.