Hmm. What a harsh title. The only reason I can pen that title is because I was one of those piano teachers that made the below mentioned mistakes for many years.

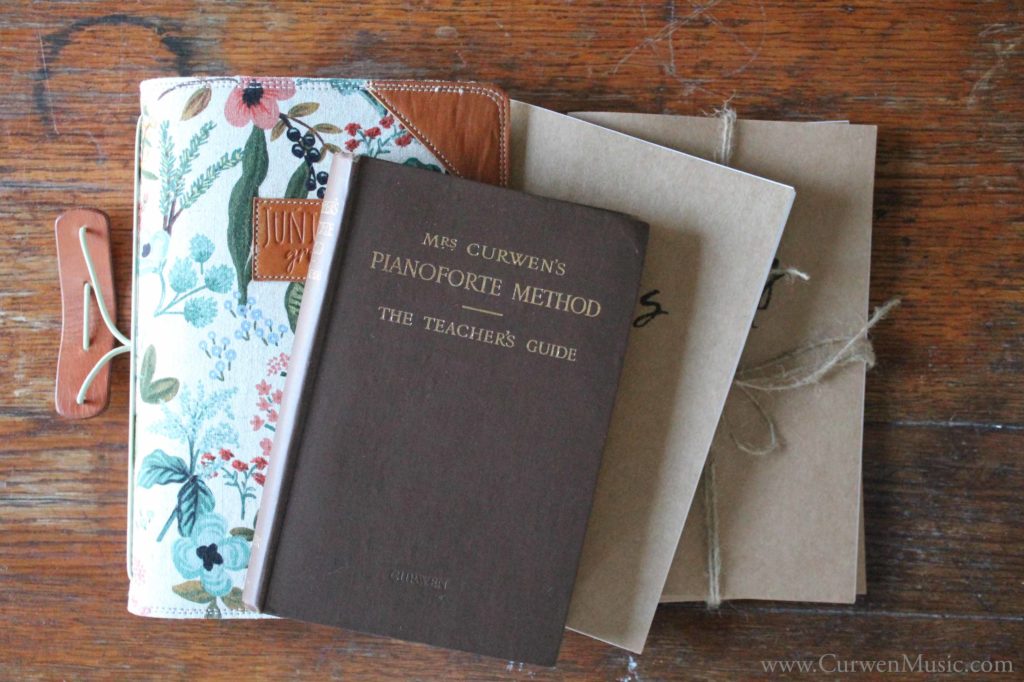

Mrs. Curwen talks fairly often of the mistakes piano teachers commonly make. I was guilty of many.

Why do I pass these mistakes on to you?

I pass them onto you because I want your child to succeed in piano. I want your child to experience the joy that comes with playing piano. I don’t want them to stop after 5th grade like so many people. I don’t want them to grow up and say, “I wish I had never stopped playing.”

Mrs. Curwen wrote out a thoughtful and intentional plan to allow students to succeed.

What are the mistakes she saw in the piano philosophies and piano teachers of the early 1900s? Are they the same still today?

1.Piano teachers start piano students too young.

Mrs. Curwen responds to the question of how old a child should before starting the piano. She says,

“and here I do not think any rules can be laid down. It is more a question of intelligence than of age; but I am sure that, as a rule, we begin too soon.” (page 2, 31st edition.)

She goes on to talk about how,

“the child of seven or eight has a great deal more motor control than the average child of five. The movement which is made easily by the one is impossible for the other.”

2. Piano teachers present difficulties of music simultaneously.

She references four processes in music that must done to read a simple tune:

- to think of the name of the note on the staff.

- to find the corresponding place on the keyboard.

- to consider what amount of time it is to occupy.

- to make up his mind which finger to use.

“When all the above-mentioned difficulties confront him simultaneously, is it any wonder that the child is discouraged and his progress slow? Is it any wonder that the young teacher, fighting against nature instead of working with nature, wears of kicking against the pricks, and longs for the time when she make take “advanced” pupils, and leave off “beginners”? Is it any wonder that the elementary teaching of the pianoforte is generally spoken of as “drudgery”?”

She goes on to solve this problem of presenting difficulties simultaneously. Much of her method is based off of present those four processed separately to the child.

3. Piano teachers don’t take time to teach the theory.

Mrs. Curwen believes that theory and practice go hand in hand. She says that

“Teachers often say ‘I have not time to teach much theory; the practical work takes all the time of the lesson.'”

She goes on to say that,

“for practice which has not theory at the back of it is but parrotlike performance, a doing something without any reason for doing it; and theory, if not illustrated and fixed by practice is a deadening and unfruitful study.”

Yet again, she solves the problem she presents in her well laid out method.

“The exercises of the Child Pianist, and its recreative pieces too, are but illustrations of the gradual unfolding of its theory.” (page 7, 31st edition.)

4. Piano teachers teach theory from a paper or blackboard.

Mrs. Curwen says over and over again that music is an art to be taught through the ear. She warns against teaching signs without sounds. In other words, if a child cannot hear or feel a pulse / beat in the music, you cannot move forward in teaching a child a quarter note. A quarter note has no true meaning until a child can hear the beat.

She says,

“Music, from first to last, is a thing of hearing, and every musical fact should reach the mind through the ear. The children should listen, compare, judge, and then do; for in music the only proof that a pupil knows something is that he can do something.”

She goes on to say, once again, in the following section of the book that,

“One of the fundamental mistakes in pianoforte teaching has been that only one sense was appealed to, and that the wrong one. Music reaches heart and brain through the ear, yet we have usually tried to teach it through the eye. It was always “look,” and never “listen.”

She uses a similar example as to the one I mention above.

“For instance, that in real tunes some sounds last for two beats and pulses and some for only one is a fact that any child can observe for himself when we direct his attention to it.”

She goes on to explain that after a child can identify a one pulse or two pulse sound, ONLY THEN do you go on to show them what a one pulse or two pulse symbol looks like. This is a quarter note and a half note.

She claims teachers make a mistake by showing a child a quarter note and a half note first and explaining what they are before allowing a child to hear the difference. The explanation of a quarter note and a half note have no meaning to a child to a child if they haven’t heard them.

I continue this list in Part II of this short series. I hope you find these helpful and encouraging.