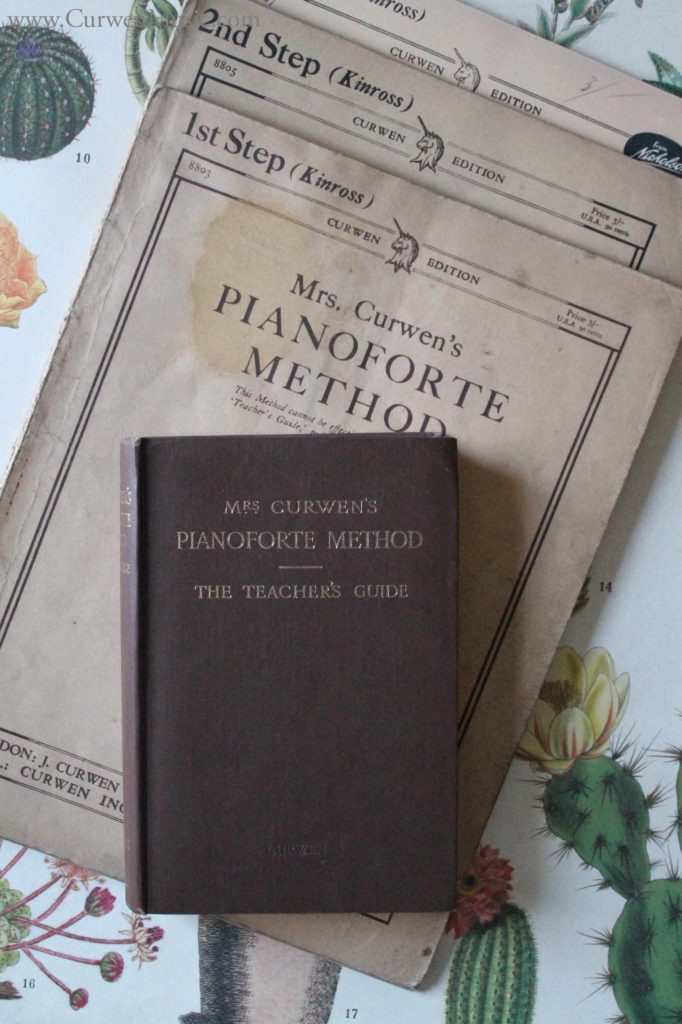

Be sure to see Part I of this short series for the first four mistakes Mrs. Curwen points out when teaching piano.

Mrs. Curwen had a watchful and observant eye when it came to children. She had their best interest in mind and pointed out some common faults of teachers, including myself, that could be made much better with a little work and thoughtfulness.

5. Piano teachers make the generalization that studying musical form is too advanced a study for beginners.

Mrs. Curwen encourages piano teachers to

“accustom the child from the beginning to notice the imitations in rhythmic and melodic “shape” and the natural “breathing places.”

This shouldn’t be something forced or difficult to accomplish in a lesson. She goes on to say how talking about music form is absolutely necessary if the child is to play simple music with intelligence.

“It is by cultivating the child’s habits of observation that we draw out that feeling for right phrasing which makes the musician almost independent of printer’s marks.” (page 17, 31st edition.)

Starting early on and this process of phrasing becomes innate to the child as they grow musically.

6. Piano teachers don’t take the time to give unbarred sentences.

What are unbarred sentences you may ask? They are simply a line of music without bar lines. The measures are not specified. It’s just a line of music with notes.

She requests pupils to copy the unbarred line of music. Then they are to add the bar lines. In the earlier levels, they are told how many beats per measure. in the later years, they are to determine that for themselves.

She says,

“pupils are seldom systematically trained to this kind of work because hard-worked teachers cannot spare time to look up suitable passages for the purpose and to write them out without bars for their pupils. Thus, for lack of material, this exercise, so useful in testing the knowledge of time-notation, is omitted; candidates for examination plunge at it, and girls of sixteen are puzzled by a test which can be done without difficulty by a child of ten who has gradually approached the standard from an easy beginning.” (page 18, 31st edition.)

7. Piano teachers don’t see the necessity for ear training in pitch.

Mrs. Curwen mentions how piano teachers are quick to neglect ear training when it comes to pitch. We piano teachers often pass that responsibility off to the singing teacher. Plus, a child can indeed play piano music without having a great ear. It’s simple to move on without ear training.

She says,

“Because this is possible, the training of the pitch-sense is too often totally neglected; and there are hundreds of pianoforte players (and teachers too) who are incapable of writing from dictation the simplest phrase, who do not realize the sounds of the notes they look at until they have played them, or recognize changes of key (by their ear) as they play.” (page 20, 31st edition.)

Oh, and what about that child who plays by ear?

“Singularly enough the possession of a quick ear is considered by some people as rather a stumbling-block in the way of learning to play the piano! ‘This child has too good an ear, and won’t look at her notes’ is a common complaint, and so this good gift of God is suppressed rather than cultivated.”

Mrs. Curwen goes on to talk about the blessings of having a quick ear. Think of the person who can naturally sing harmony because their ear allows them to sing. Then when they see the notation or actually study why harmony is harmony, they come to “a revelation of reason for effects with which he is already acquainted.”

8. Piano teachers give students music that is too hard for them.

“The playing of the recreative music therefore is always the outcome of the child’s own knowledge; for if he has mastered the contents of each lesson he will be able to read at sight the duets which illustrate it, and the consciousness of growth in independent power keeps his interest alive.” (page 9, 31st edition.)

In the past, I always had the tendency to give my students music that was just a bit difficult for them. I figured with enough practicing, they can move forward just a bit each week with their songs.

What I did instead was likely frustrate my students. They never reaped the reward or the satisfaction that comes with playing something well.

Mrs. Curwen revisits the subject of recreative music much later in her book. She quotes the late Sir Charles Halle who said,

“Let your exercises and studies be always a little beyond you, but your pieces well within your power.”

Mrs. Curwen entirely agreed with that statement. She goes on to say that,

“To give a pupil a piece just a little beyond his powers is either to mislead or to discourage him. If he is satisfied with his own performance his artistic judgement is being misled; if he does not satisfy his own ideal he is discouraged.” (page 149, 14th edition.)