Hey friends,

I am asked this question often: How does Mrs. Curwen’s method compare to other piano teaching methods?

I’ll answer this question as best as I can (in a somewhat generic sense). As you compare methods, feel free to graciously comment with your own thoughts and interpretations. I’m curious what you think as well!

I’ll preface this article with saying I’m not a piano pedagogy expert. My strength is music theory. It’s what I studied in college, and when I approach musical study, my thinking naturally bends toward the principles of music theory.

I have not studied other methods from the inside out like I have with Mrs. Curwen’s method. I probably don’t give other methods a fair evaluation simply because I’ve studied so much more on Curwen than I ever did with any other method.

After studying music in college, I taught piano for almost ten years prior to beginning my study on Mrs. Curwen’s method.

Are my findings below a result of my lack of diligence in teaching, researching, and understanding piano pedagogy? Or are they a result of the method books I was pulling off the shelf?

Probably a bit of both. But I am ultimately responsible for the training, passion, and inspiration I pass on to my students. (…whether now or ten years ago.)

What did I discover once I started implementing Mrs. Curwen’s method?

1. I found significant gaps in my students’ knowledge.

There were major gaps in my students’ understanding of music. All I had to do was informally discuss the Preliminary Exam questions with my Level 3 students, and I realized they were missing so much foundational knowledge.

If you glance through the 1st Step Book (the book used once the Preliminary Lessons are finished and mastered), the first lesson has a child naming notes on the entire staff. NONE of my students could do this fluently. I had students I had been teaching for years who had no tools to figure out notes that spanned the entire staff. I had not given them the tools for that.

2. I was not laying a good musical foundation.

My students’ powers of execution were not in line with their understanding of theory. I was simply training my students to read notes.

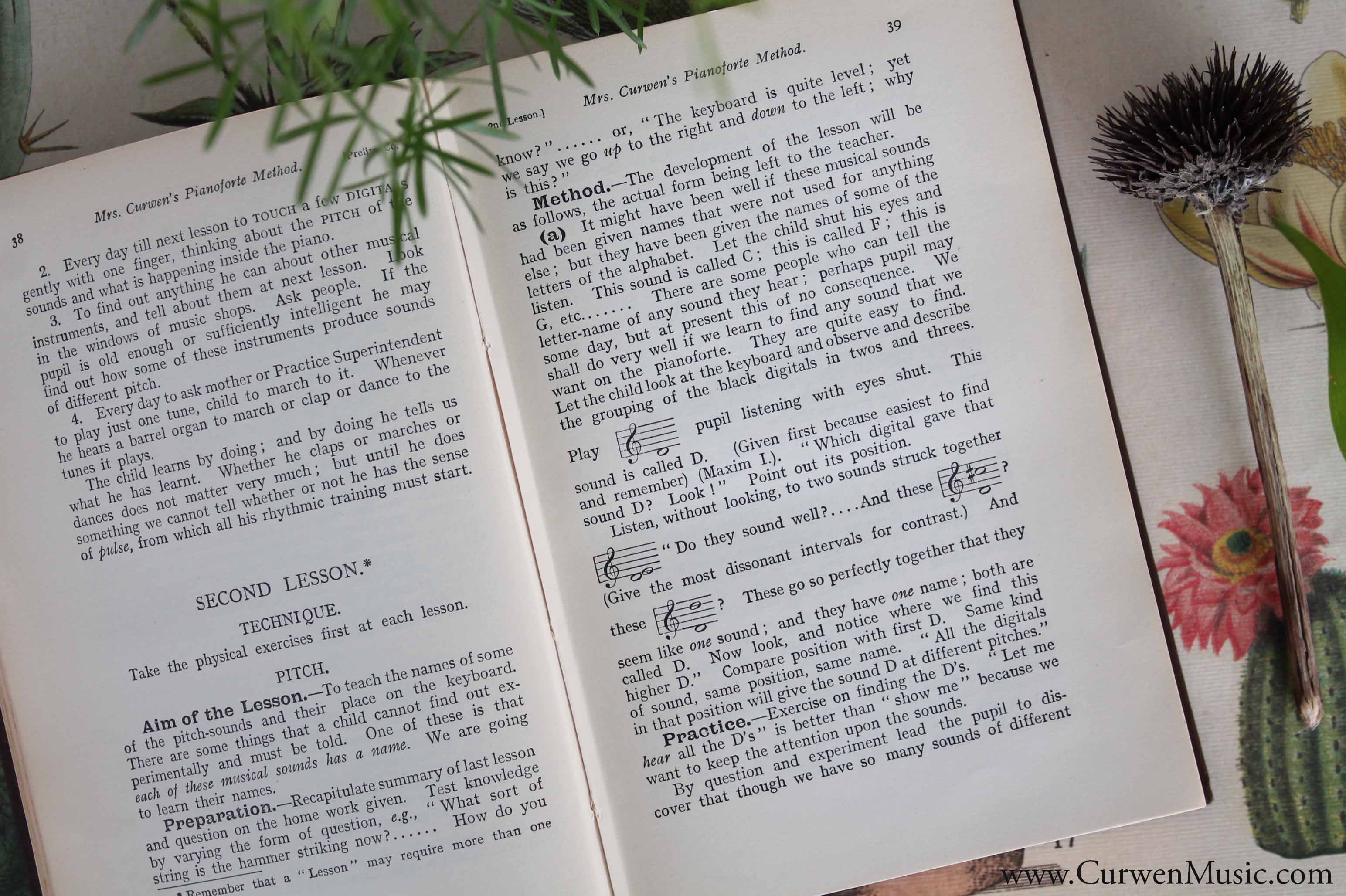

“One of the fundamental mistakes in pianoforte teaching has been that only one sense was appealed to, and that the wrong one. Music reaches heart and brain through the ear, yet we have usually tried to teach it through the eye. It was always ‘look,’ and never ‘listen.’ Children were introduced to notation before they had consciously observed any of the musical phenomena which the notation symbolizes. They should learn those facts of pitch and time by listening, comparing, judging, naming, and then use notation as a means of expression. (see Maxim 2.) A pupil so taught is not a slave to notation, but its master.”

3. Mrs. Curwen requires a mastery of skill before moving on to the next thing.

This has become so crucial for my beginner students. I’ve seen an immense amount of change and progress as I’ve gone backward to work on mastering basics.

For example, in the Preliminary Lessons, Mrs. Curwen has the students naming sounds on the piano going up in thirds and down in thirds. (The interval of a third is very foundation to her method because she uses it to teach the framework of the staff.)

Before ever introducing how a sound is written down, the student masters where the sounds are on the piano and what the names of all the sounds are. In other words, the students know the keyboard well. The can find octaves. They can name the sounds going up by step and down by step. They can name them going up in thirds and down in thirds.

They always master one thing before moving to the next.

4. When Mrs. Curwen teaches something, she teaches it from multiple angles.

Mrs. Curwen’s multi-faceted approach eliminates the possibility for misunderstanding on the part of the student.

Think about how Mrs. Curwen teaches rhythm. Here’s a very brief synopsis of how a student goes about learning time notation.

The student:

a.) Clap or march while listening to music.

b.) Identify the pulse or throb of music.

c.) Listen and identify the regularly measured accented pulse.

d.) Identify two, three, or four pulse music.

e.) Listen for one, two, three, or four pulse sounds.

f.) Sing time-names for one, two, three, and four pulse sounds.

g.) Draw a symbol for one, two, three, and four pulse sounds.

h.) Listen to a melody and notate out the rhythm.

You first sing rhythm with the time names. Then you learn to write the symbols for a pulse. Then you sing and play the rhythm you see. Then you write the symbols of the rhythms you hear.

5. Mrs. Curwen’s exercises were written with a definite purpose and aim.

Let’s look at interval exercises. Mrs. Curwen has a book devoted specifically to interval exercises. These exercises, even though simple for most children, open their eyes to the powers of understanding intervals.

Understanding how intervals sound and how they look gives students another valuable tool in reading and hearing music. It also teaches them to play without looking down at their fingers.

These exercises have purpose. They aren’t aimlessly wading students through patterns of notes without aim or reason.

6. The music Mrs. Curwen chose for children was written for children.

The music she provided was not simplified pieces originally written for adults or advanced pianists. Think about the character of classical music. It’s music that tells a story with emotion and expression and forward forward progression. Sometimes when evaluating music, I ask myself if it’s twaddle music. We hear Miss Mason use the word twaddle in regards to the books our children read. Is there such a thing as twaddle in music?

7. I was attempting to win my students over with fun and familiar songs instead teaching them to play beautifully.

Do you know what I’ve discovered is most satisfying to piano students? They love it when they can look at a piece of music and play it. What’s even better? They love it when they can play the story and expression behind the music.

I do my best to give them beautiful music. I now give them music with character and expression. I try to always give them music they can play!

Before encountering Curwen, I’d sort through books at the local piano store looking for music I thought my student would be inspired to play because they knew it from the radio or their favorite movie. But this type of music is going to be severely watered down for a child to play and the child may encounter multiple hand position changes to play the melody they are familiar with.

8. I was giving students music beyond their powers.

This is still likely my biggest weakness. I tend to give students music that I think they should be able to play instead of what they are capable of playing.

By the end of the semester, my students should be able to play a few pieces of music beautifully. I’ve never seen this come to fruition until now.

“Never allow a pupil to shirk at difficulty, and do not be satisfied with saying, or thinking, that a piece is played ‘very well for a child.’ It should be played artistically, or not at all. The simplest music, if played artistically, is worth listening to, and the consciousness that his little piece is listened to with pleasure, because he plays it as the composer meant it to be played, will give a child an interest in his music which nothing else can give.” (page 364, 31st edition.)

9. She never asks a student to play something they’ve never heard before.

I started playing for my students for the first time ever.

Mrs. Curwen has a book called Illustrative Tunes. This book is full of songs for the teacher to play.

Here’s an example of how this book is used: a child has learned a quarter, half, dotted half, and whole note, and they are being introduced to an eighth note at their lesson. Instead of explaining the eighth note, I’d instead play a song full of eighth notes. They can listen for them. They learn to identify them before I’d ever ask them to play them.

After they can hear an eighth note, then I’d request them to play an eighth note. Then they’d write an eighth note. Then they’d read an eighth note. Then they’d write one from dictation – again learning the concept from multiple angles.

10. Mrs. Curwen’s method is a long term and patient method. Results will not likely be immediate.

The Preliminary Lessons will likely take an entire semester for an average seven year old child to complete well. Unless the child is interested in learning a song by rote, they will not be playing any songs for a full semester! But boy, when the results come to surface, it is immensely encouraging for the teacher AND STUDENT!

“Now sight-playing, even of the simplest tune, requires not only a familiarity with symbols representing certain elementary facts of Pitch and Rhythm, but also the power of realizing these two classes of symbols instantaneously and of doing two things at once. Children are often expected to begin here, and hence their difficulties. We must begin further back. There is a stage in the pupil’s development which precedes the use of symbols; a stage in which he has to investigate for himself (guided by the teacher) these elementary facts.” (page 32, 31st edition.)

Hi!

In my own children, I’ve noticed that when they are made to “learn” the formalities, their desire to learn ends. Our oldest (now 28) took maybe 6 months of piano. She was excited to learn the Christmas songs because she learned the entire songs and could already hear them in her head, but after the New Year, when they really buckled down with the book and learning the scale, etc. she was “done” with piano. Now, though, she plays many instruments (piano, banjo, violin, guitar, etc.) by ear. All of our children play by ear. How does a piano teacher, using this or any other method, balance the desire to learn and the “hearing” of the music without killing the desire by learning the formalities? I grew up in public school band classes, and I do realize the importance of learning the formalities. Just curious, as we still have young children and I’ve always found the lessons to be almost like pulling teeth vs. just sitting down and playing… Hope this makes sense. Thanks!

Hi Lisa, this makes total sense. Anything that profits is going to take a bit of labor. Most things with joy and delight come with discipline and work. It’s hard for a small child to understand that. So yes, I understand sometimes lessons are like pulling teeth.

First off, I think it’s great your children play by ear!! That is such a great skill to have and such a blessing. If they can play by ear, it means they already know how to listen and imitate. Wonderful!

If I have a student that seems to dread lessons, I first ask myself, ‘what can I change?’

Am I talking too much? Are the lessons too long? Are topics covered in a brief manner? Do I move quickly from one topic to another in order to keep the child engaged? Is the child experiencing any reward or satisfaction? Is it visible to the child that he’s making progress? Am I asking the child to do something they can’t do? Do I have realistic expectations set for this particular student? Is the mom graciously holding the student accountable to practice?

For ten years of teaching piano, I attempted to win children over with ‘fun’ songs, kind words, and colorful piano books.

But what really brings the greatest delight and satisfaction to a child? Playing a song well that is easy for them to play. Just like I enjoy sitting down and playing through the hymn book, they want to sit down and simply play through their books as well.

How do I take a child to the place where they can play a song beautifully?

1. Giving them good and right tools to learn to write down the music they hear. If they can write it down, they can read it.

2. Giving them music to play that’s well within their powers. It’s not satisfying to play music that is always stretching and difficult to play. The joy comes in playing something with ease.

3. Never asking them to play something they haven’t heard. It’s hard to teach an eighth note if they’ve never heard an eighth note played before.

4. Giving them a musical education where their powers of theory stay constant with their powers of playing music. The opens a gateway of opportunities for musical experiences.

That being said, I don’t do everything right, and I still have students that don’t look forward to piano lessons. But I continue patiently teaching and inspiring as best as I know how.

Thanks for leaving a comment and feel free to ask more questions or email for any further feedback!

Thank you for replying! And you summed it up beautifully with:

“But what really brings the greatest delight and satisfaction to a child? Playing a song well that is easy for them to play. Just like I enjoy sitting down and playing through the hymn book, they want to sit down and simply play through their books as well.”

That’s it! They want to just sit down and play without the drudgery of going thru the formalities and that’s the hump I’ve found. K was enjoying just sitting down and playing songs but didn’t want to go through the mechanics of “The BOOK”. (And honestly, the others have followed suit). If I leave them to their instruments, they “do their thing” and it just comes. Having come from being taught music theory, I understand the importance of being able to see the music and read/understand it.

Thank you so much for your thorough thoughtful reply.

Lisa